Extractive Industries Auditors Toolkit

Introduction to Extractive Industries

According to the World Bank, about 3.5 billion people live in countries rich in oil, gas, or minerals and these natural resources play a dominant role in 81 countries. Africa alone is home to about 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, 10% of the world’s oil, and 8% of the world’s natural gas.Extractive industries (EI) operate at multiple scales and use a variety of methods. For mineral extraction, EI includes small-scale and Artisanal Mining as well as large-scale industrial mining operations. For oil and gas extraction, methods may include conventional oil extraction on-shore or off-shore, as well as unconventional methods, such as fracking, coal bed methane, or underground coal gasification.EI can create jobs directly and indirectly and generate significant revenue. Revenue from the oil, gas, and mining industries has tremendous potential to become a financial base for infrastructure development, social service delivery, and to lift people out of poverty. Effective governance and oversight of EI may help ensure that these benefits of resource development are realized, and that the resources are extracted in a sustainable manner.

These pages provide information for auditors who are new to EI, including links to additional resources by the World Bank, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, and audit organizations such as AFROSAI-E (African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions – English).

What are Extractive Industries?

Extractive industries involve the removal of raw materials from the earth to be used by consumers. These raw materials are processed into products that are used in a wide variety of sectors, including energy, transportation, and manufacturing. The WGEI has defined the scope of its work to include oil, gas, and mining activities.

Oil and Gas: According to the International Human Resources Development Corporation (IHRDC) —an oil and gas industry training company—oil and gas provide the world’s 7 billion people with 60 percent of their daily energy needs. These resources, known as fossil fuels, originated from the decomposition of organic material compressed over millions of years. Oil and gas resources are located both onshore and offshore.

Figure: Oil and Natural Gas Formation

Mining: Minerals extracted from the ground are critical in many sectors of the world economy, including manufacturing, construction, medicine, and agriculture. For example, metals such as iron, copper, and nickel are often used in home construction, vehicles, and electronic devices. Minerals such as antimony, lithium, and potash are used in medications. Phosphate is used as a fertilizer, and fluorite is found in consumer products, such as ceramics and toothpaste.

Economic and social benefits of extractive industries can be significant.

According to IHRDC, world energy markets are continually expanding, and companies spend billions of dollars annually to maintain and increase their oil and gas production. Over 200 countries have invited companies to negotiate for the right to explore their lands or territorial waters, hoping that they will find and produce oil and gas, create local jobs, and provide billions of dollars in national revenues.

According to the World Bank, wealth on the scale experienced in some resource-rich states can generate significant positive development outcomes. Even for states with modest petroleum or mineral deposits, the outcomes from resource development and corresponding investment could be transformative.

For context, in the first decade of the 21st century, investments in mining were estimated at about US$80 billion, with much of this destined for iron ore and copper. According to the International Energy Agency, investments in fossil fuel supply reached US$450 billion in 2017.

For lower-income countries, revenues from exploiting resource wealth could exceed official aid flows substantially. In principle, such revenues could unlock the constraints of foreign exchange, savings, and public finance and support a broad range of social and physical infrastructure priorities common to developing states, according to the World Bank’s EI Source Book.

Extractive industries can have major adverse impacts and may pose challenges for governments.

Many have noted that EI development outcomes are frequently less robust and beneficial than expected.

The EI sectors can have major adverse environmental and social impacts. In the past, these issues have not always been well recognized or addressed by governments, but good practice has improved greatly since the end of the 20th century, according to the EI Source Book.

Many have noted that development outcomes in the EI sector are frequently less robust and beneficial than expected. Moreover, the outcomes can become highly damaging to the resource-rich state. Resource-rich developing states typically underperform economically relative to their peers that are not resource rich. Further, they may experience environmental degradation and have more social and political instability and violent conflict. Taken together, factors such as these have led some to describe the outcomes as the “resource curse” or the “paradox of plenty.”

Wealth on the scale experienced in some resource-rich states can generate significant positive development outcomes.

Avoiding or reducing these impacts depends on appropriate legal instruments, adequate enforcement, and fiscal structures that incentivize good behavior by investors, while recognizing the costs involved and internalizing them.

7 Steps of the EI Value Chain, Explained

According to the World Bank, the EI value chain provides a framework for the governance of the EI sector. The value chain is meant as a tool to support countries’ efforts to translate mineral and hydrocarbon wealth into sustainable development.

In its 2015 guidance, AFROSAI-E (African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions – English) expanded the World Bank’s original five step EI value chain to include the steps of establishing the legal framework and resource exploration, as shown in the figure below.

Figure: The 7 step EI Value Chain

Figure sources: Summarized from the World Bank, The Extractive Industries Sector: Essentials for Economists, Public Finance Professionals, and Policy Makers, and AFROSAI-E, Guideline: Audit Considerations for Extractive Industries.

Key Considerations When Auditing EI

Selecting and determining the scope of EI audits can be a challenge for SAIs. There are many ways of examining EI activities, depending on the type of extractive industry, the stage of a resource’s development, and the government’s relationship to EI within your country, among other factors. These pages provide information to help guide the audit scoping process for auditors who are new to EI, through four key steps, identified by INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing:

Figure: Four Key Steps for Scoping EI Audits

Figure source: Summarized from INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Auditing Mining: Guidance for Supreme Audit Institutions, 2010

Identify extractive industries and related effects

As a first step to developing an audit approach, it is important to understand the scope of extractive industries within the country. For example, SAIs should determine which minerals are mined, the geographic extent of mining activities, the type of mining performed (e.g., artisanal or commercial), and the extent to which mining contributes to the national economy. Additionally, it is important to consider any short- and long-term economic, environmental, and societal effects related to the EI activity. There are several resources available to help auditors determine which extractive industries may be operating in their country:

![]() EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI and provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g. gas, oil, gold).

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI and provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g. gas, oil, gold).

![]() NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals. Resource Projects is a clearinghouse of information collected by the Natural Resources Governance Institute on over 2,200 individual resource projects across the world. These data may include information on the EI company involved, the type of material extracted (e.g. oil), the status of the project, recent payments to governments, and production statistics.

NRGI: The Natural Resource Governance Institute helps people to realize the benefits of their countries’ endowments of oil, gas, and minerals. Resource Projects is a clearinghouse of information collected by the Natural Resources Governance Institute on over 2,200 individual resource projects across the world. These data may include information on the EI company involved, the type of material extracted (e.g. oil), the status of the project, recent payments to governments, and production statistics.

OpenOil: OpenOil is an open source data repository of over three million compliance documents related to the oil, gas, and mining industries. Information includes EI concession agreements and contracts in about 70 countries.

OpenOil: OpenOil is an open source data repository of over three million compliance documents related to the oil, gas, and mining industries. Information includes EI concession agreements and contracts in about 70 countries.

Identify the government’s relationship to these activities

Governments play an important role in regulating extractive industries and its social, economic, and environmental effects. Specifically, governments have a variety of legal authority and tools that they use to oversee extractive industry activities. To develop an audit approach, it is important to understand the scope of the government’s authority and regulation of extractive industries within the country. There are several resources available to help auditors determine the government’s response to EI in their country:

![]() EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI, and most of these countries provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g., gas, oil, gold).

EITI: The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is a global standard to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources. 52 countries participate in EITI, and most of these countries provide data on EI activities within their borders. These data may include information on EI company operations, geographic region of operations, revenue generated, and the type of material extracted (e.g., gas, oil, gold).

United Nations: The United Nations maintains a database of treaties and their participants, which can be searched to see which treaties your country has signed. There are a wide variety of international treaties, conventions and protocols that could be relevant to EI, such as the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

United Nations: The United Nations maintains a database of treaties and their participants, which can be searched to see which treaties your country has signed. There are a wide variety of international treaties, conventions and protocols that could be relevant to EI, such as the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Policy, Legal, and Contextual Framework has links to mining laws and regulations in 69 countries, and oil laws and regulations in 50 countries.

EI Source Book: The EI Source Book is intended as a guide to good-fit practice in the management of oil, gas, and mining sectors across the EI value chain. The Policy, Legal, and Contextual Framework has links to mining laws and regulations in 69 countries, and oil laws and regulations in 50 countries.

Choose the appropriate audit type and topic

According to the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions, public-sector auditing is essential because it provides independent and objective assessments concerning the stewardship and performance of government policies, programs or operations. SAI roles in auditing EI vary by country and depend on the SAI’s legislative mandate.

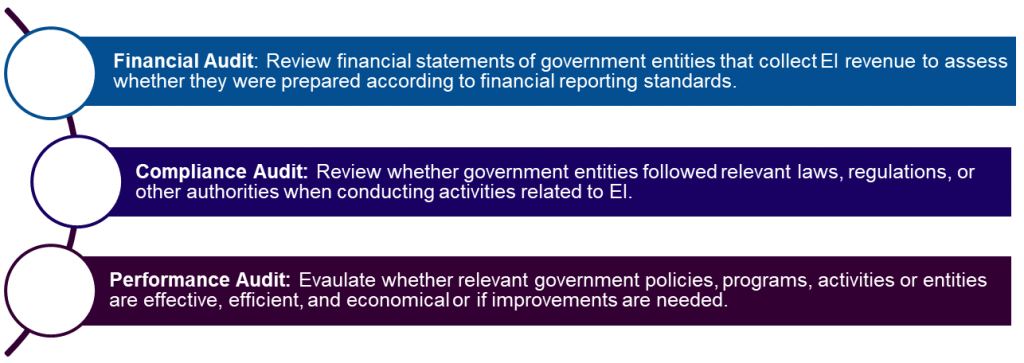

Generally, there are three types of audits: financial, compliance, and performance, as described in the figure to the right.

Figure: Three types of audits

Figure sources: Summarized from INTOSAI’s Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Auditing Mining: Guidance for Supreme Audit Institutions, 2010

When choosing an audit topic, SAIs should assess how their work will be used and where it could have the greatest impact on improving the oversight of EI. Key questions to consider are:

- How will the audit be used and will it have an impact?

- Does the SAI have jurisdiction over the topic or entities involved and access to the necessary information?

- Is evidence available and are there suitable sources of criteria to compare efforts against?

Determine the audit approach

According to the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions, the overall audit approach is a central element of any audit. It determines the nature of the examination to be made and defines the necessary information and data and the audit procedures needed to obtain and analyze them.

The design process explores the variety of options available for collecting and analyzing information and can help auditors determine an audit approach that will best address the audit objective within available resources. A design matrix is one tool to help auditors identify the necessary information for each research question, as shown below.

Table: Using a design matrix to determine audit approach

| Audit objective: What do we wish to achieve through the audit? | ||||

| Audit risk: Internal or external factors that may affect the audit | ||||

| Research questions | Criteria and information sources | Scope and Methodology | Limitations | Potential Findings |

| What do you want to know? | What information do you need to answer the question? | How do you plan to obtain the information and what will you do with it? | What is not possible? | What do you expect to find? |

| Questions should be: · Clear · Specific · Objective · Measurable · Doable |

Identify the evaluation standard and evidence needed: · Physical · Documentary · Testimonial · Analytical |

. Establish the boundaries of the audit (e.g., organizations, timeframes) . Describe the plan to gather and evaluate the information in the second column and otherwise conduct the work. |

Try to anticipate any conditions that might limit your ability to answer the questions, obtain the information, or conduct the analyses described in the third column. | Describe potential findings and how the audit may affect stakeholders. |

Sources: Content summarized from the ISSAI Standard 300 and Appendix to ISSAI 5520.[Note: ISSAI Framework is migrating to IFPP]

Artisanal and small scale mining (ASM)

Artisanal and small scale mining (ASM) is a form of mineral extraction whereby individuals typically work independently with only small hand tools or basic machinery—and often outside of the formal legal framework and without regulatory oversight, to extract and sell minerals such as gold, silver, diamonds, and other precious gem stones. According to the World Bank’s Communities and Small Scale Mining (CASM) initiative, understanding the complex nature of ASM is critical to effectively implementing any measures to mitigate the negative and optimize the positive effects of these activities in the context of sustainable development.

ASM is a complex web of issues; spanning policy and regulation, environment, human health, culture and society, and economics. Governmental responses to ASM are typically intended to mitigate the potential harmful effects of ASM to human health and the environment, improve the lives of individuals and communities engaged in ASM and living in poverty, and prevent instances of violence and armed conflict associated with ASM.

Figure: How prevalent is ASM?

Figure source: Summarized from the International Institute for Environment and Development report Responding to Challenges of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining.

According to a report by the International Institute for Environment and Development, ASM is prevalent worldwide and can have a significant economic impact. For example, in the Central African Republic, two-thirds of its people are estimated to rely directly or indirectly on artisanal diamond mining and conservative estimates suggest it injects as much as $144.7 million into the economy. In Bolivia, mining makes up approximately 40 percent of current income from exports, 32 percent of which comes from ASM, with 85 percent of the mining sector’s total employment in small mining cooperatives and mines. Additionally, ASM is responsible for between 15 – 20 percent of global minerals and metals. Within this, the sector produces approximately 80 percent of all sapphires, 20 percent of all gold and up to 20 percent of diamonds.

Key Features of ASM

Figure source: Summarized from the International Institute for Environment and Development report Responding to Challenges of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining.

Challenges of ASM

Some of the inherent structural challenges facing artisanal mining include:

- Governance: Weak legislation, policies, and implementation and other government marginalization or repression of miners, including political exclusion from decision-making; lack of legal protection for land and resource rights; generally poverty-driven decision-making with focus on the short-term, may cause or prolong social/armed conflict.

- Societal Impacts: Reliance on mining in ASM communities due to vulnerability and marginalization based on culture or demographic group, with low barriers to entry into informal or illegal ASM with minimal health and social protections; associated uncontrolled migration of workers. Environmental hazards, such as mercury pollution, from ASM may have lasting effects in the area of mining and larger implications.

- Lack of Information: There is limited baseline or census data on ASM workers and communities. Further, because much of ASM activities occur outside of the legal framework, monitoring the supplies and revenue of ASM is particularly challenging and results in limited tax benefits for governments.

Key guidance and further information

OECD: The OECD issued guidance, “OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains from Conflict-Affected and high Risk Areas,” as part of its efforts to further the responsible sourcing of minerals.

OECD: The OECD issued guidance, “OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains from Conflict-Affected and high Risk Areas,” as part of its efforts to further the responsible sourcing of minerals.

World Bank: The World Bank sponsored the Communities and small-Scale Mining (CASM) initiative. While the program has since ended, many of the documents may be found at http://www.artisanalmining.org. The World Bank also partnered with Pact to develop DELVE, a platform for artisanal and small-scale mining data that was piloted in 2017. More information about this initiative can be found here.

World Bank: The World Bank sponsored the Communities and small-Scale Mining (CASM) initiative. While the program has since ended, many of the documents may be found at http://www.artisanalmining.org. The World Bank also partnered with Pact to develop DELVE, a platform for artisanal and small-scale mining data that was piloted in 2017. More information about this initiative can be found here.

IPIS: The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) is an independent research institute that provides information, analysis, and capacity enhancement to support those actors who want to realize a vision of durable peace, sustainable development and the fulfillment of human rights. IPIS has published papers on ASM.

IPIS: The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) is an independent research institute that provides information, analysis, and capacity enhancement to support those actors who want to realize a vision of durable peace, sustainable development and the fulfillment of human rights. IPIS has published papers on ASM.

Washington Post: The Washington Post published an extensive multi-media article on cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Washington Post: The Washington Post published an extensive multi-media article on cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo.